by Samuel Rose Parkinson

Franklin, Idaho, 1911

by Samuel Rose Parkinson

Franklin, Idaho, 1911

I am not much of a public speaker, neither am I a good hand at telling a story in the presence of so many people, but I can assure you my heart is full of love and tenderness toward the few remaining veterans of the little colony that suffered so many privations and hardships in founding this settlement. I am proud that I have lived to see this happy day and wish all the noble little band were here with us to share its pleasures.

I remember well the journey through Cache Valley, the three days in the south field, sometimes called Camp Cove, and the day we pulled across Spring Creek and made our camp on the west bank, a little east of where we now are. It was the 14th of April, 1860, just two days after I turned 29 years of age. I had a wife and five children and our little colony consisted of about 15 families. We were all acquainted with each other and all being of the same faith and sacred motive, we lived and associated almost as one harmonious family. We enjoyed each other's confidence and love and were extremely happy in the midst of all dangers and hardships.

We had all our earthly possessions with us, consisting in the main of a team and wagon, a cow, provisions to last a few weeks, a few simple and crude tools and farm implements, some seed wheat and a few garden seeds.

We soon laid out our fort, and I think I was as good a civil engineer as there was in the camp, and that wasn't saying much for the rest of them. Our only instruments for this work was the north star and a carpenter's square. With this aid we surveyed our streets, laid out the blocks and lots, each block consisting of eight city lots of an acre and a quarter each. We drew out our city lots as well as the field lots of ten acres each, and soon turned to plowing and digging ditches for irrigating. As soon as we had a few days to spare, the time we spent in providing shelter for our families. The best houses were built of rough logs with dirt floors and dirt roofs. We had no lumber, no window glass, no store locks or hinges, no furniture of any description, except that which we made with our own crude tools.

Our food consisted principally of fish and game and roots, and a few of the more fortunate indulged in an occasional meal of boiled wheat. We kindled the fires by striking together two pieces of flint, and then neighbors would borrow coals of fire from each other. Matches were seldom seen. The wool from the backs of the sheep was carded, spun, and woven into rough cloth for our clothes. When we were short of wool, milk sheep were killed and their wool was used. Skins of wild animals were made into clothing. Our wives and daughters became experts at carding and spinning and weaving and dressmaking all of our clothes. I had a family of boys and my wife was handy with the needle. We all wore buckskin trousers and shirts and beaver caps and rawhide boots. The girls wore linsey dresses made by their own hands.

I presume my boys and girls wouldn't care to appear before this audience today in what they considered their best in those days, but they were contented and were good children and they know how to appreciate better things by reason of that valuable experience.

I can tell you of some thrilling adventures we passed through in those early days. Scenes and conditions that would try the hearts of the bravest men, but thanks to kind Providence they are passed. We did the best we could and I would not like to try it over again. We may not do so well the second time.

The old log schoolhouse was built in the summer of 1860, before we were all supplied with houses for our families. (I think Mrs. Hannah Comish was the first teacher employed.) I had the honor of being one of the first trustees and soon after became a student in the school myself. We were interested in the education of our children and we did the best we could to make good citizens of them. How well we succeeded may be judged from the appearance and character of the men and women composing the majority of this vast audience, who are descendants of the pioneers of this and the adjoining settlements founded in this valley under similar conditions and circumstances.

Our schoolhouse was used also as a place of worship, and for our amusements, and in time of trouble with Indians it was converted into a garrison and then a hospital and so it served our purpose well. There was no one to complain about us teaching good religion in our schoolhouse, and what a blessing that was.

Everything in those days was managed and done under the direction of our ecclesiastical authorities, and it was well done, too. Great wisdom was exercised by our leaders. They were loyal and true and we were all devoted to the best interest of each other, seeking to establish ourselves where we could dwell in peace and rear and educate our children in the fear and love of God, teaching them to honor our country's flag, to love the truth, and to adopt into their lives such principles as shall make for the cleanest and purest and noblest manhood and womanhood and the highest possible standard of civilization and good citizenship. Such was our religion. We tried to exemplify it. We taught it to our children, by word and by act. We were serious, conscientious, and determined. We did the best we could. We have nothing to regret and solemnly dedicate the result to the future.

I thank you.

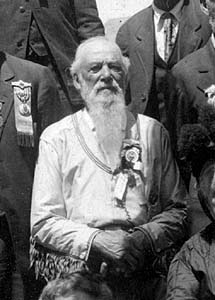

Franklin pioneers at the 1910 Founders Day, one year before this speech.